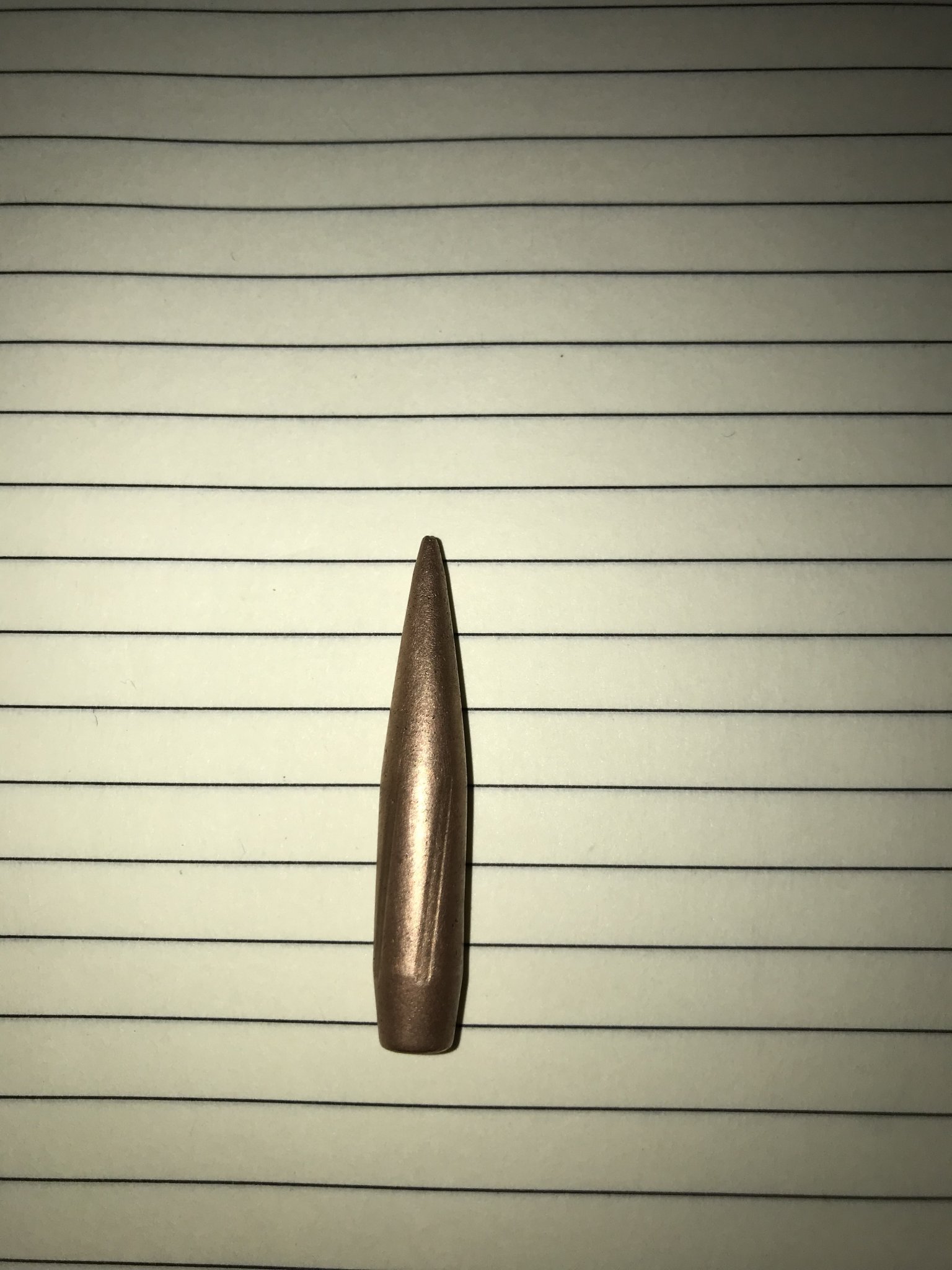

After doing some shooting yesterday at 1580 yards, 4000 DA, 45 degrees F, 6-10 mph wind mostly a head wind, my Buddy was able to recover one of the misses from my 6.5 saum 150 smk very well preserved. Looking over the bullet over made me think about some of what I’ve been reading on here lately and engraving from rifling, it is very consistent and jacket held up fine to that. What I’m curious about is all the pitting on the bullet. Is this from inside the bore, during flight, or all happening in the impact of a soft dirt backstop? If it happens early on this has to have some effect on flight. If it happens at the impact why are they noticeable on the boat tail and even the base? Based on AB bullet was traveling 1400 FPS at Target with 653 pounds of energy. Hopefully pictures show up well enough to see the pitting I’m referring to. Anyway thought it was relevant and interesting with some recent topics. Let me know your thoughts.

- Thread starter Gilly

- Start date

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

My random, unscientific guess is that possibly the high heat and pressure the projectile encounters during flight leads to the pitting; possibly due to oxidation.

I recently watched a video on the X-15 ultrasonic aircraft which showed a model aircraft in a supersonic wind tunnel literally have the wings melt off due to heat from the friction caused by the air. Supersonic aircraft are made of materials much better suited to deal with heat than copper and lead.

I recently watched a video on the X-15 ultrasonic aircraft which showed a model aircraft in a supersonic wind tunnel literally have the wings melt off due to heat from the friction caused by the air. Supersonic aircraft are made of materials much better suited to deal with heat than copper and lead.

Hi,

Do you have access to a high powered digital microscope by chance?

It would be interesting to see those pits under large zoom. Could see if it was gun powder, carbon, dirt from air, jacket deterioration etc etc.

Sincerely,

Theis

Do you have access to a high powered digital microscope by chance?

It would be interesting to see those pits under large zoom. Could see if it was gun powder, carbon, dirt from air, jacket deterioration etc etc.

Sincerely,

Theis

I can almost guarantee it's from striking the dirt upon impact. I have been surprised before but I doubt anything in the air for 2-3 seconds of flight time is pitting a copper alloy jacket. Always fun when you find them!

At our 1000 yard range I see all types of bullets, the huge, all lead ones from black powder "Quigley" rifles are my favorite, they are almost pristine. Huge chunk of lead the size of your thumb!

At our 1000 yard range I see all types of bullets, the huge, all lead ones from black powder "Quigley" rifles are my favorite, they are almost pristine. Huge chunk of lead the size of your thumb!

Far fetched, but could it have been from the impurities in the metal acting out because of the heat induced during the firing process?

I was thinking something like this as well. If Hornady changed their tips because they were melting in flight, it makes sense that the copper jacket could get hot enough to burn off some of the impurities. I have recovered several bullets from out past 1,500 yards, but none looked that perfect. All were dented or deformed in some way.

That's cool! How far off did it go from the target? Was there a backstop or something?

That’s from 1580 yards and we have a dirt mound that was pushed up with a loader behind the target. It came out of that mound.

In developing my new solid copper ULD bullet, we have fired a bunch of them into the deep end of a swimming pool and recovered them quickly. We are primarily reading the bullet engraving marks and the sooting patterns to check bullet obturation from different rifling patterns, but have noticed that certain powders produce gasses which tarnish the bright copper where the hot gasses touched it. I suspect a reactive sulfur compound is involved. The bullet is primarily heated by bore friction during firing, secondarily by conduction from the hot propellant gasses, and the thirdindarily by aerodynamic friction. The bullet is pretty warm when it impacts the target (but not nearly enough to melt even pure lead). Plastic tips are sometimes softened or melted in flight, however. You should wear gloves in recovering just-fired bullets.

The pitting in question here is due to impact in sand or loamy soil. Impact speed was probably about Mach 1.0. The bullet bases would not be pitted unless the bullet tumbled in the dirt, which these probably did.

The pitting in question here is due to impact in sand or loamy soil. Impact speed was probably about Mach 1.0. The bullet bases would not be pitted unless the bullet tumbled in the dirt, which these probably did.

Last edited:

Yup, this.Heat from in-flight friction softens the copper jacket. Dirt then has more chance of embedding itself in softer copper. I also agree with Jim Boatright , the spots on the boat tail are from tumbling once hitting the dirt mound.

Copper melts at 1984F. Lead melts at 621F. Copper has very high thermal conductivity, so heat absorbed by copper will quickly transfer to the underlying lead, limited somewhat by lead's lower TC, Only the highest temperature polymers make it past 675F before melting/decomposing. So of the components in a tipped, jacketed bullet, the copper is least likely to melt. The jacket is thin and its resistance to deformation depends in part on the underlying lead that is softer, melts far lower and makes up the bulk of the bullet's mass.

Put that all into the context of what Jim said:

"The bullet is primarily heated by bore friction during firing, secondarily by conduction from the hot propellant gasses, and the thirdindarily by aerodynamic friction. The bullet is pretty warm when it impacts the target (but not nearly enough to melt even pure lead)."

As you know, the engraving of rifling survives bullet flight, and often, impact. So air friction heating is probably not causing the pitting. Copper has a Moh's hardness in the about 3, lead is around 1.5, quartz is about 7 and and silica sand runs in the 6 to 7 range. So a typical berm has particles that are way harder than those of a projectile.

Put that all into the context of what Jim said:

"The bullet is primarily heated by bore friction during firing, secondarily by conduction from the hot propellant gasses, and the thirdindarily by aerodynamic friction. The bullet is pretty warm when it impacts the target (but not nearly enough to melt even pure lead)."

As you know, the engraving of rifling survives bullet flight, and often, impact. So air friction heating is probably not causing the pitting. Copper has a Moh's hardness in the about 3, lead is around 1.5, quartz is about 7 and and silica sand runs in the 6 to 7 range. So a typical berm has particles that are way harder than those of a projectile.

Somewhere I have a picture of a bullet in flight. It's been moved twice to new computers so I may never find it again. It was taken with a thermal camera. The areas with the highest temperatures were the area on the front of the ogive surrounding the meplat. About 25% of the ogive. The other is the rifling grooves. I don't know any of the details, caliber, velocity, distance from the muzzle etc.

I think aerodynamic heating is not an issue at all for any of us mortals. Supersonic aircraft need special materials only due to the time spent at speed. A couple seconds doesn't count. F111 fighter/bombers were temp limited for speed and at or around mach 2 they got about 15 minutes of supersonic cruising. At that point the warning lights came on and the pilot slowed down to reduce heating. The difference between a couple seconds and a few minutes is huge.

The military is using artillery that fire heavy projectiles miles away. They travel at supersonic speed for the greater part of that travel and yet they feel no need to protect the explosives from heating due to aero friction.

I don't think the pitting is due to outgassing of impurities from heat. In fact, the idea of impurities that would burn off is very unlikely. The copper sheet used to make bullets is very pure. It has to be or the forming/drawing characteristics would be way off for its use. In addition the cups are annealed at pretty high temp more than once to keep them from cracking or tearing in the processing. Since the lead isn't melting in the bullet the temps must be below its melting point of about 675 deg F. Annealing temps are over 800 deg F so my guess is that the heat has nothing to do with the external appearance of the bullets recovered from long range (or short range) shooting.

One last thing to remember, even though the velocity of the bullet drops off fairly quickly the spin does not. Shooting these lovely long telephone poles accurately takes a fairly fast twist so the bullets are spinning fast, over 180,000 rpm fast. This spin doesn't slow much in the time it takes to go from the firing line to 1500 yds. When they hit the ground they're spinning fast enough to sand off a goodly amount of copper in dirt. Looking at the bullet pictured above you can see evidence of the spin and note that the rifling grooves look rounded and worn. Fresh fired bullets usually have pretty sharp grooves, its the impact and spin that rounded those off. Shoot into a swimming pool and recover the bullets.....you'll see the difference.

Frank

The military is using artillery that fire heavy projectiles miles away. They travel at supersonic speed for the greater part of that travel and yet they feel no need to protect the explosives from heating due to aero friction.

I don't think the pitting is due to outgassing of impurities from heat. In fact, the idea of impurities that would burn off is very unlikely. The copper sheet used to make bullets is very pure. It has to be or the forming/drawing characteristics would be way off for its use. In addition the cups are annealed at pretty high temp more than once to keep them from cracking or tearing in the processing. Since the lead isn't melting in the bullet the temps must be below its melting point of about 675 deg F. Annealing temps are over 800 deg F so my guess is that the heat has nothing to do with the external appearance of the bullets recovered from long range (or short range) shooting.

One last thing to remember, even though the velocity of the bullet drops off fairly quickly the spin does not. Shooting these lovely long telephone poles accurately takes a fairly fast twist so the bullets are spinning fast, over 180,000 rpm fast. This spin doesn't slow much in the time it takes to go from the firing line to 1500 yds. When they hit the ground they're spinning fast enough to sand off a goodly amount of copper in dirt. Looking at the bullet pictured above you can see evidence of the spin and note that the rifling grooves look rounded and worn. Fresh fired bullets usually have pretty sharp grooves, its the impact and spin that rounded those off. Shoot into a swimming pool and recover the bullets.....you'll see the difference.

Frank

Heat from in-flight friction softens the copper jacket. Dirt then has more chance of embedding itself in softer copper. I also agree with Jim Boatright , the spots on the boat tail are from tumbling once hitting the dirt mound.

Hi,

Do you have access to a high powered digital microscope by chance?

It would be interesting to see those pits under large zoom. Could see if it was gun powder, carbon, dirt from air, jacket deterioration etc etc.

Sincerely,

Theis

I have access to a SEM and a good digital optical microscope if you wanna send it to me I could take some photos in the name of science.

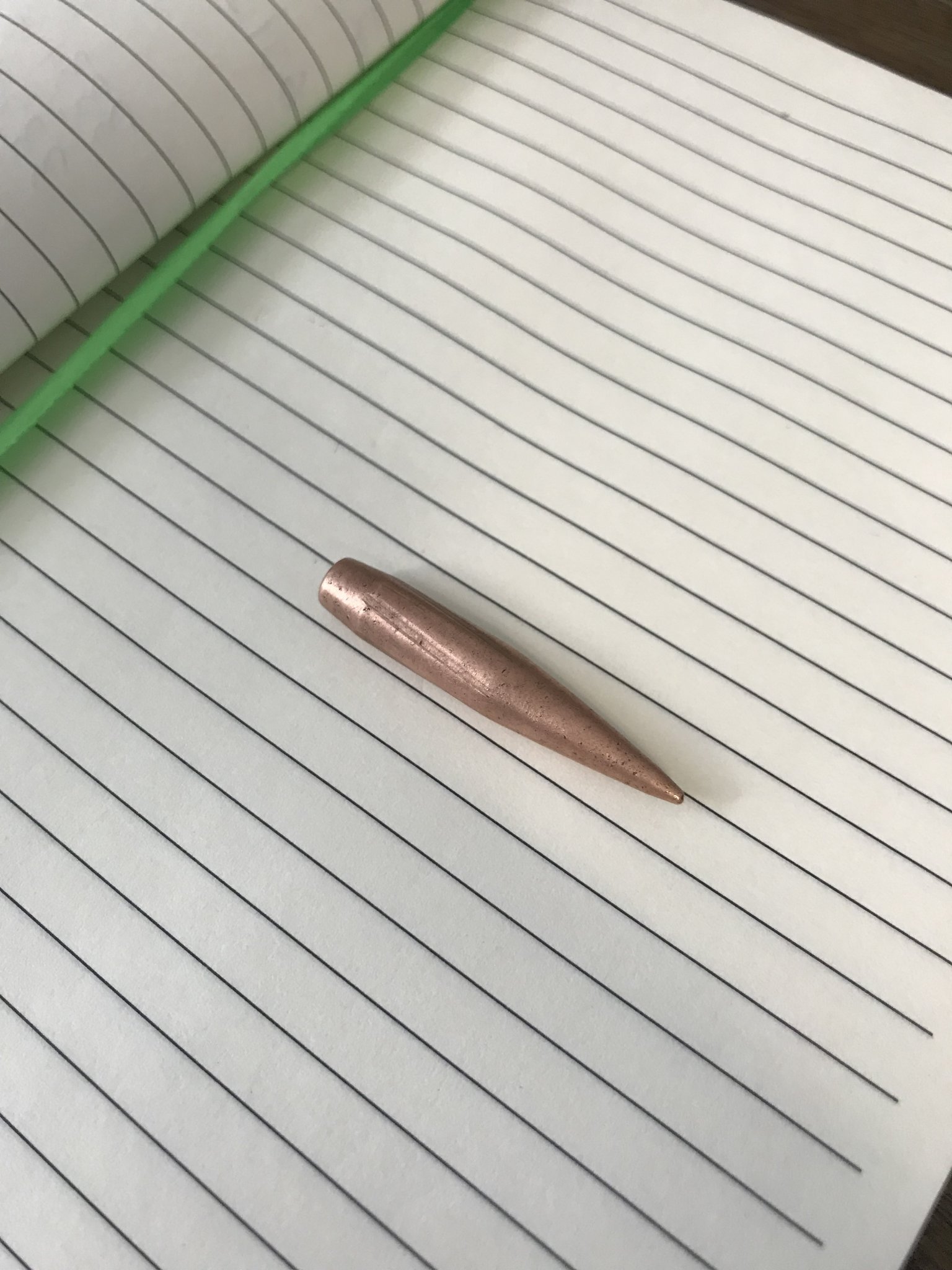

Recovered at 4000 yards in NM

Just to clarify, I don't think it's dirt from the air. While Copper melts at 1875F, it does not hold much strength as it heats up. And, yeah, just a few seconds of supersonic friction can heat the copper up. Not to the point of melting, just softening. Making it easy for dirt to leave pits in it.Heat from in-flight friction softens the copper jacket. Dirt then has more chance of embedding itself in softer copper. I also agree with Jim Boatright , the spots on the boat tail are from tumbling once hitting the dirt mound.

If the lead isn't melting the copper isn't softening. Just the way it is. I've been working with silver, copper, brass and gold for jewelry since the 70's and you have to heat copper up to about 800 deg to get it soft enough to do anything. Lead melts at about 675 F depending on alloy. Its not melted in the barrel or in flight so the copper isn't heating up enough to do any damage....it doesn't even anneal at bore temps.

Frank

Frank

Then you would probably know that copper isn't all that hard to begin with....If the lead isn't melting the copper isn't softening. Just the way it is. I've been working with silver, copper, brass and gold for jewelry since the 70's and you have to heat copper up to about 800 deg to get it soft enough to do anything. Lead melts at about 675 F depending on alloy. Its not melted in the barrel or in flight so the copper isn't heating up enough to do any damage....it doesn't even anneal at bore temps.

Frank

Hard relative to what? Compared to air it is really hard. Compared to diamonds it is really soft. For the purposes of the original discussion it is hard enough that there isn't much likelyhood of it being pitted and damaged in flight. There is high likelyhood of damage due to impact with the ground. Heating has nothing to do with either possibility because we have established through verifiable means that it is not heating enough to soften the copper jacket. That is what I'm trying to say.

I still say probably an old one that has been sitting in the mound and deteriorating. There is pitting on the base of the bullet. I can't imagine how that would happen from a front on impact with the mound.

Edit, Just read @Jim Boatright post about tumbling in the dirt.. I would think there would be some deformation to the soft bullet if it tumbled hard enough to pit the sides and base like that, no?

Edit, Just read @Jim Boatright post about tumbling in the dirt.. I would think there would be some deformation to the soft bullet if it tumbled hard enough to pit the sides and base like that, no?

Last edited:

Pure copper in its annealed state has a yield strength of about 18,000 psi. It readily work hardens to 40 ksi or even 60 ksi. Work hardened copper tools were used by prehistoric people to fell trees and carve wood. Bronze and brass alloys are stronger still. The gilding metal bullet jackets are about 95-percent copper (Cu) and 5-percent zinc (Zn), and are thoroughly work hardened in the drawing and bullet point-forming processes.

Dan Warner turns my prototype ULD bullets from 99.9-percent copper which is "half hard." They are very tough and withstand firing at high muzzle speeds from large overbore cartridges through very fast-twist rifling. There is no need for gain-twist rifling. The narrow rear driving band of these bore-riding bullets spins them up to over 6,000 rev/second with no problems. Jacketed lead cored bullets would not hold together in flight at these spin-rates.

Dan Warner turns my prototype ULD bullets from 99.9-percent copper which is "half hard." They are very tough and withstand firing at high muzzle speeds from large overbore cartridges through very fast-twist rifling. There is no need for gain-twist rifling. The narrow rear driving band of these bore-riding bullets spins them up to over 6,000 rev/second with no problems. Jacketed lead cored bullets would not hold together in flight at these spin-rates.

I still say probably an old one that has been sitting in the mound and deteriorating. There is pitting on the base of the bullet. I can't imagine how that would happen from a front on impact with the mound.

Edit, Just read @Jim Boatright post about tumbling in the dirt.. I would think there would be some deformation to the soft bullet if it tumbled hard enough to pit the sides and base like that, no?

I have recovered lots of WWI and WWII-era jacketed rifle bullets which have eroded out of old berms. Some of them are in remarkably pristine condition. The copper jacket material does not pit when oxidized. They just get darker colored with age and weathering. The exposed lead-alloy cores do show more oxidation stress, however, developing the white, powdery lead oxide coating seen on recovered Civil War bullets.

D

Deleted member 10043

Guest

Need a picture of the impact area and a sample of the soil. Also, was it just laying there on the ground or buried.

I was picturing more of a galvanic reaction from something in the soil rather than oxidation. Just a guess though. Some of the putting looks crater-like but some of it does look to be from an impact where you can see a raised edge on one side.I have recovered lots of WWI and WWII-era jacketed rifle bullets which have eroded out of old berms. Some of them are in remarkably pristine condition. The copper jacket material does not pit when oxidized. They just get darker colored with age and weathering. The exposed lead-alloy cores do show more oxidation stress, however, developing the white, powdery lead oxide coating seen on recovered Civil War bullets.

Weird but we’ve pulled so many MTACs and later Warner 256s out from the 2000-2200m range and never saw anything but amazingly preserved projectiles - even the 285 Amax would often their tips intact

Even after impact with plates (image below) jacketed and solid remnants look good on the non impact surface.

Have other bullets laying around somewhere intact from misses

Even after impact with plates (image below) jacketed and solid remnants look good on the non impact surface.

Have other bullets laying around somewhere intact from misses

Last edited:

D

Deleted member 10043

Guest

Okay, real talk. Post the muzzle velocity, BC, and so forth so we can determine the angle it hit the berm. Angle of the berm is important too. Bullet appears to be sand blasted. Yes, even the flat ass end got it too in the vortex it created on impact. This is terminal ballistics and is only the end of exterior ballistics though the latter played a large role getting it there under the right conditions. What is the sectional density of that bullet?

As an aside, look at @Lowlight pic above that landed at over twice the distance. The OP bullet has no blunt nose trauma like his does. Also, the angle of the nose trauma is indicative of a bullet coming down at a much steeper angle with less energy. It also slowed to a stop much quicker. Thus, less energy and time to blast the jacket surface. But there is still some present on the longer range bullet.

As an aside, look at @Lowlight pic above that landed at over twice the distance. The OP bullet has no blunt nose trauma like his does. Also, the angle of the nose trauma is indicative of a bullet coming down at a much steeper angle with less energy. It also slowed to a stop much quicker. Thus, less energy and time to blast the jacket surface. But there is still some present on the longer range bullet.

Last edited by a moderator:

I think aerodynamic heating is not an issue at all for any of us mortals. Supersonic aircraft need special materials only due to the time spent at speed. A couple seconds doesn't count. F111 fighter/bombers were temp limited for speed and at or around mach 2 they got about 15 minutes of supersonic cruising. At that point the warning lights came on and the pilot slowed down to reduce heating. The difference between a couple seconds and a few minutes is huge.

The military is using artillery that fire heavy projectiles miles away. They travel at supersonic speed for the greater part of that travel and yet they feel no need to protect the explosives from heating due to aero friction.

I don't think the pitting is due to outgassing of impurities from heat. In fact, the idea of impurities that would burn off is very unlikely. The copper sheet used to make bullets is very pure. It has to be or the forming/drawing characteristics would be way off for its use. In addition the cups are annealed at pretty high temp more than once to keep them from cracking or tearing in the processing. Since the lead isn't melting in the bullet the temps must be below its melting point of about 675 deg F. Annealing temps are over 800 deg F so my guess is that the heat has nothing to do with the external appearance of the bullets recovered from long range (or short range) shooting.

One last thing to remember, even though the velocity of the bullet drops off fairly quickly the spin does not. Shooting these lovely long telephone poles accurately takes a fairly fast twist so the bullets are spinning fast, over 180,000 rpm fast. This spin doesn't slow much in the time it takes to go from the firing line to 1500 yds. When they hit the ground they're spinning fast enough to sand off a goodly amount of copper in dirt. Looking at the bullet pictured above you can see evidence of the spin and note that the rifling grooves look rounded and worn. Fresh fired bullets usually have pretty sharp grooves, its the impact and spin that rounded those off. Shoot into a swimming pool and recover the bullets.....you'll see the difference.

Frank

Frank, if you ever want to know a bullet's spin-rate in flight, just first calculate its initial spin-rate as MV/Tw (in feet per turn), then multiply that by an exponential decay factor given by exp[-tof/(cal/0.0321)] where "tof" is time of flight in seconds and "cal" is the bullet caliber in inches. So, that 6.5 mm bullet was still spinning at 78 percent of its original spin-rate after flying for 2 seconds. The spin decay is very nearly exponential in time, but not exactly so. The difference is about +/- 0.5 percent early in flight while dynamic pressure is greatest.

My copper bullets do not seem to mind being launched at 300,000 to 600,000 RPM, with the higher spin-rates for the smaller calibers.

Jim Boatright

EDIT: I have a 5-inch twist 6.5 mm barrel on order from Bartlein. It will use 5R rifling, for which they are grinding a new cutter to handle this twist. I paid them $240 to grind the new cutter. They quoted 6 months delivery.

Last edited:

Shoot ballistic gel from a mile lol

This is a Flat Line 151 gr. 7mm that was shot from a 284 Winchester from 1,900 yards. the one next to it is in pristine (ish) condition.

Hundreds, if not a thousand flat line down range and this is the only time I've seen this effect. Image is from 2012.

Hundreds, if not a thousand flat line down range and this is the only time I've seen this effect. Image is from 2012.

its from impact with dirtHi,

Do you have access to a high powered digital microscope by chance?

It would be interesting to see those pits under large zoom. Could see if it was gun powder, carbon, dirt from air, jacket deterioration etc etc.

Sincerely,

Theis

Here is a picture of some of my 338-caliber monolithic copper ULD prototype bullets made by Dan Warner. The top bullet is un-fired for comparison. The other bullets were fired at about 3000 fps from my 10-twist Krieger barrel with conventional 6-narrow-land "square-cut" rifling. The bullets were fired at about 45 degrees downward into the deep end of a swimming pool and promptly recovered. The second bullet from the top had no base-drilling, and the lower ones were base-drilled to the depths shown by the black annotation marks. Notice the big difference in gas sealing effectiveness between the un-drilled bullet and the ones which were base-drilled along their axes. The copper ogives curled over even more with higher water impact speeds. The rifling lands index pretty well with the curved noses because the muzzle-to-water distance was fairly constant in these firing tests. The curl was consistent upon entering the water at 45 degrees. I was mainly concerned with reading the marks left by the lands on the engraved rear driving bands, but discovered this big discrepancy in gas sealing as an unexpected test result. Note the evidence of elastic (temporary) bullet expansion due to porting the base pressure into the interior of the base-drilled bullets. The elastic bullet expansion stops right at the drill shoulder depth. The OD's of the fired bullets match those of the un-fired example above.

Jim,Here is a picture of some of my 338-caliber monolithic copper ULD prototype bullets made by Dan Warner. The top bullet is un-fired for comparison. The other bullets were fired at about 3000 fps from my 10-twist Krieger barrel with conventional 6-narrow-land "square-cut" rifling. The bullets were fired at about 45 degrees downward into the deep end of a swimming pool and promptly recovered. The second bullet from the top had no base-drilling, and the lower ones were base-drilled to the depths shown by the black annotation marks. Notice the big difference in gas sealing effectiveness between the un-drilled bullet and the ones which were base-drilled along their axes. The copper ogives curled over even more with higher water impact speeds. The rifling lands index pretty well with the curved noses because the muzzle-to-water distance was fairly constant in these firing tests. The curl was consistent upon entering the water at 45 degrees. I was mainly concerned with reading the marks left by the lands on the engraved rear driving bands, but discovered this big discrepancy in gas sealing as an unexpected test result. Note the evidence of elastic (temporary) bullet expansion due to porting the base pressure into the interior of the base-drilled bullets. The elastic bullet expansion stops right at the drill shoulder depth. The OD's of the fired bullets match those of the un-fired example above. View attachment 6992703

As you noted on the second bullet, the difference in sealing, how well does the bullet stay true (added: in the barrel). I guess I'm seeing where there could be a difference accuracy capability as the short length of the driving band might not hold the bullet as true to the barrel? Maybe also a situation where you ask how much accuracy increase vs. how much friction/drag in the barrel are we trying to avoid?

Last edited:

Jim

Sorry for the host of questions...

Looking at your drilled projectiles in the photo, and seeing how they expanded do you believe that was a result from not leaving a thick enough side-wall (for lack of a better term)? I shot prototype solids for Noel Carlson years ago (2008 to 2010 or 2011), including tail drilled versions of those projectiles and we never saw them react the way that yours have. In our case it may well be that the hole drilled stopped at the forward edge of the engraving bands, so we didn't notice there might be "extra" expansion and engraving than we expected to see. Interesting. Did you per chance have a magneto speed chronograph on the rifle when the drilled projectiles were shot? Did they run slower or produce more copper in the barrel? You more than doubled the amount of engraving surface.

Jeffvn

Sorry for the host of questions...

Looking at your drilled projectiles in the photo, and seeing how they expanded do you believe that was a result from not leaving a thick enough side-wall (for lack of a better term)? I shot prototype solids for Noel Carlson years ago (2008 to 2010 or 2011), including tail drilled versions of those projectiles and we never saw them react the way that yours have. In our case it may well be that the hole drilled stopped at the forward edge of the engraving bands, so we didn't notice there might be "extra" expansion and engraving than we expected to see. Interesting. Did you per chance have a magneto speed chronograph on the rifle when the drilled projectiles were shot? Did they run slower or produce more copper in the barrel? You more than doubled the amount of engraving surface.

Jeffvn

Those bullets were fired and recovered in several different firing tests using different powders. The clean undrilled bullet was fired with VV-N560, and the dulled bullets were fired with Alliant RL-25 which produces excess sulfides and dull the copper where it came into contact. No MS chrono was used in that much water spray. All of the loads produced 3000 fps or slightly less. The earlier purpose of base-drilling was for improved mass distribution leading to higher initial gyroscopic stability in aeroballistic flight. We stumbled on the bullet expansion side-effect when looking at interior ballistics and went back to look at the saved bullets. Sure enough, the base-drilled bullets showed greatly improved gas sealing. So now we are doing the minimum amount for gas sealing and also getting a little better gyroscopic stability. The amount of expansion desired is controlled by drill diameter selection. I went from 0.166-inch down to 0.125-inch drilling to minimize the weight reduction penalty while still allowing enough bullet expansion. None of this affects accuracy or forward-flight aerodynamics, which are excellent. The main advantage of better gas sealing is allowing single-digit MV spreads to be more readily achieved for better ELR shooting.

I am attaching my paper on Interior Ballistics with Copper Bullets which explains their gas sealing, shot-start pressure, and rotational effects.

I am attaching my paper on Interior Ballistics with Copper Bullets which explains their gas sealing, shot-start pressure, and rotational effects.

Attachments

I thought you would be running your virsion of the lutz moler nose ring at match the shock wave of the front to the back on that bullet to help with transonic are you planning on running that design ???Those bullets were fired and recovered in several different firing tests using different powders. The clean undrilled bullet was fired with VV-N560, and the dulled bullets were fired with Alliant RL-25 which produces excess sulfides and dull the copper where it came into contact. No MS chrono was used in that much water spray. All of the loads produced 3000 fps or slightly less. The earlier purpose of base-drilling was for improved mass distribution leading to higher initial gyroscopic stability in aeroballistic flight. We stumbled on the bullet expansion side-effect when looking at interior ballistics and went back to look at the saved bullets. Sure enough, the base-drilled bullets showed greatly improved gas sealing. So now we are doing the minimum amount for gas sealing and also getting a little better gyroscopic stability. The amount of expansion desired is controlled by drill diameter selection. I went from 0.166-inch down to 0.125-inch drilling to minimize the weight reduction penalty while still allowing enough bullet expansion. None of this affects accuracy or forward-flight aerodynamics, which are excellent. The main advantage of better gas sealing is allowing single-digit MV spreads to be more readily achieved for better ELR shooting.

I am attaching my paper on Interior Ballistics with Copper Bullets which explains their gas sealing, shot-start pressure, and rotational effects.

My design goal was to increase the maximum supersonic range greatly, not to design a good subsonic bullet. Unfortunately, I don't know how to do both simultaneously. I expect the 375-caliber version of my bullet to stay supersonic all the way to the 2-mile targets at Whittington this year. Has anyone ever done that before? With a bullet weight of only 335-gr and an estimated G7 BC of 0.481, these 375's could be fired at 3600 fps or more from several cartridges. Maximum supersonic range would be a lot less in cold, dry, sea-level air. From a 7.0-inch twist barrel, the initial gyroscopic stability is 3.1, which should allow hyper-stable flight to be achieved very early.

I have heard mention of Lutz Moler, but have not seen any of his work. Can you suggest where I can find it?

I have heard mention of Lutz Moler, but have not seen any of his work. Can you suggest where I can find it?

I think his name is lutz moeller or something like that unless you can read German its going to be hard to do research on himMy design goal was to increase the maximum supersonic range greatly, not to design a good subsonic bullet. Unfortunately, I don't know how to do both simultaneously. I expect the 375-caliber version of my bullet to stay supersonic all the way to the 2-mile targets at Whittington this year. Has anyone ever done that before? With a bullet weight of only 335-gr and an estimated G7 BC of 0.481, these 375's could be fired at 3600 fps or more from several cartridges. Maximum supersonic range would be a lot less in cold, dry, sea-level air. From a 7.0-inch twist barrel, the initial gyroscopic stability is 3.1, which should allow hyper-stable flight to be achieved very early.

I have heard mention of Lutz Moler, but have not seen any of his work. Can you suggest where I can find it?

I think his name is lutz moeller or something like that unless you can read German its going to be hard to do research on him

Hi,

Well Lutz information is on a couple different website he has. I have no idea as to the age of the information as I haven't heard anything with him since the FAILED "Viking" projectiles he made for a few people in the USA years ago.

http://kjg-munition.de/index.html

http://lutzmoeller.net/1/Suche.php

Sincerely,

Theis

Well Lutz information is on a couple different website he has. I have no idea as to the age of the information as I haven't heard anything with him since the FAILED "Viking" projectiles he made for a few people in the USA years ago.

http://kjg-munition.de/index.html

http://lutzmoeller.net/1/Suche.php

Sincerely,

Theis

correct I think he was the one who was credited with designing the transonic nose ringHi,

Well Lutz information is on a couple different website he has. I have no idea as to the age of the information as I haven't heard anything with him since the FAILED "Viking" projectiles he made for a few people in the USA years ago.

http://kjg-munition.de/index.html

http://lutzmoeller.net/1/Suche.php

Sincerely,

Theis

correct I think he was the one who was credited with designing the transonic nose ring

Hi,

That would be correct unless my memory is wrong.

The Viking bullet is below: (BUT from everything I read...it did not work) Maybe he has a new version, I do not know.

https://lutzmoeller.net/1/9,5-mm/LM-119.php

Sincerely,

Theis

boy I see some serious issues with that but some good ones as well .Hi,

That would be correct unless my memory is wrong.

The Viking bullet is below: (BUT from everything I read...it did not work) Maybe he has a new version, I do not know.

https://lutzmoeller.net/1/9,5-mm/LM-119.php

View attachment 7006319

Sincerely,

Theis

Last edited:

Hi,

So I found the original information about the nose ring from Lutz...it was back in 2012 but public in like 2013.

In 2013 he also made a hunting projectile with base drilled along with nose ring design.

Sincerely,

Theis

So I found the original information about the nose ring from Lutz...it was back in 2012 but public in like 2013.

In 2013 he also made a hunting projectile with base drilled along with nose ring design.

Sincerely,

Theis

there is your drilled base James interesting information Thanks Thies Mr. Swamplord that's what we were talking about the other nightHi,

So I found the original information about the nose ring from Lutz...it was back in 2012 but public in like 2013.

In 2013 he also made a hunting projectile with base drilled along with nose ring design.

View attachment 7006367

Sincerely,

Theis

Those bullets really look badass! no pun intended!there is your drilled base James interesting information Thanks Thies Mr. Swamplord that's what we were talking about the other night

Hi,

@badassgunworks

What is unique, especially for you and swamp is that projectile is designed to mushroom and break off the "base" at the ring. So you get the front section that mushrooms followed by the solid mass "base" into the wound channel.

Sincerely,

Theis

@badassgunworks

What is unique, especially for you and swamp is that projectile is designed to mushroom and break off the "base" at the ring. So you get the front section that mushrooms followed by the solid mass "base" into the wound channel.

Sincerely,

Theis

Similar threads

- Replies

- 13

- Views

- 693

- Replies

- 95

- Views

- 5K

- Replies

- 23

- Views

- 4K

Training Courses Training Class at Big River Ballistics in Morton, Ms

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 147