Developing skill as an art through conscious practice.

We build skill through conscious practice—by observing our own shots, learning from experience, and refining those lessons over time. Real skill comes from mindful engagement with reality: discovery through struggle, and validation of every principle until it proves repeatable and true. This kind of practice also builds genuine confidence, because reality confirms what we know; it repeats itself and aligns with our lived experience. This article serves as a cornerstone for RifleKraft students and readers—a guide to a mindset that embraces mindful practice as the path to understanding and growth.

The minds illusion

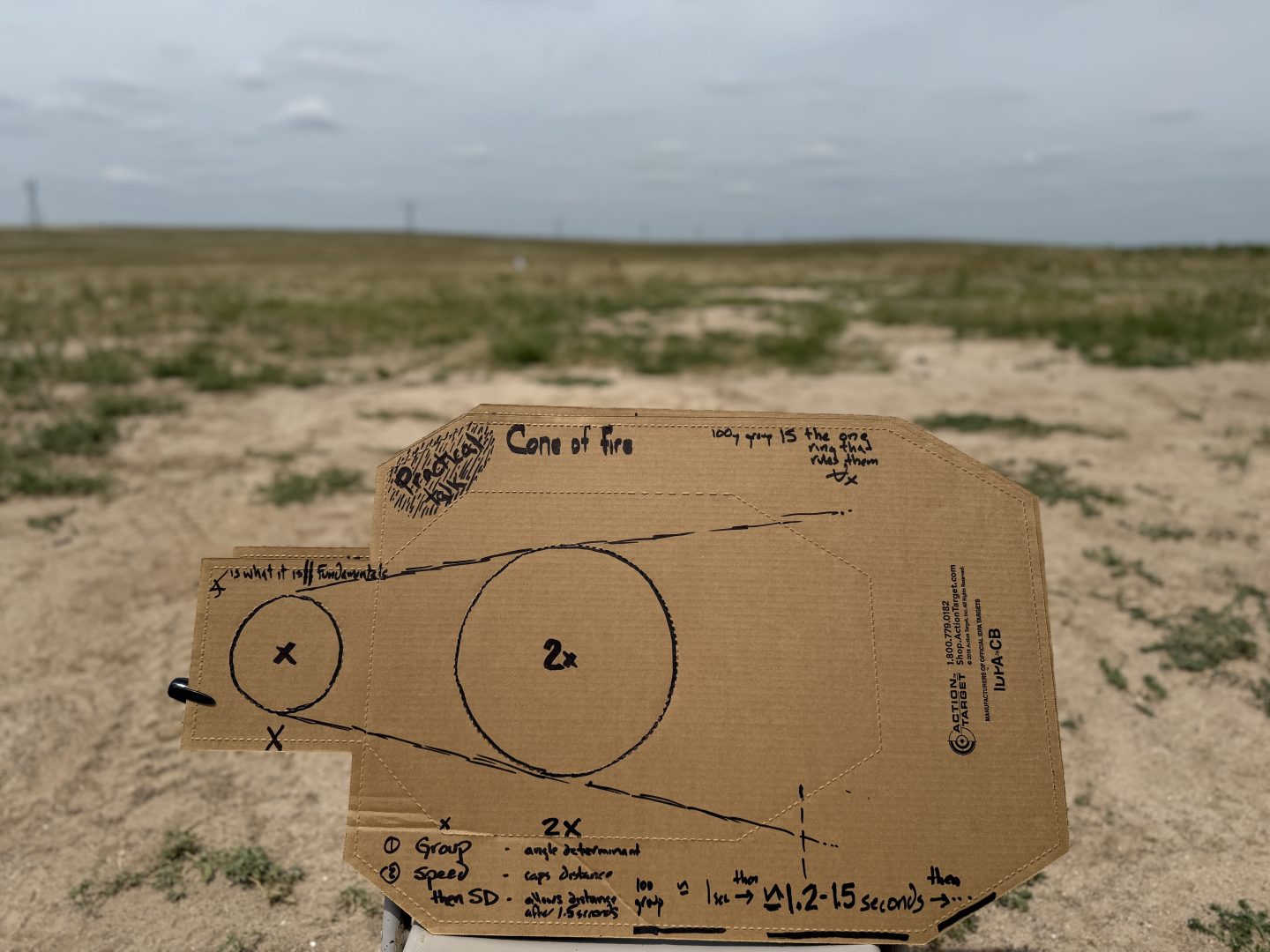

When you train for a goal, illusions that promise shortcuts can easily pull you off course from your true destination. For example a video game simulates fishing with beautiful graphics, shortened delays, and detailed equipment. Yet games cannot reproduce the subtle proprioceptive experience of holding a rod, feeling the bite, the breeze or smelling the water. The same danger exists in shooting: shortcuts that feel efficient. Whether dumping a case of ammo or training by watching someone else talk about it on clean edited video. They remove the very struggle where skill is born. Conscious practice means you must focus on what you are going to do and make sure that your training includes all of the elements you can add for the most realism. In replicating context and skills, measuring progress, and experimenting with the details we can raise the odds of success and growth over time.

The shortcut trap

In the shooting world, myths abound: ‘shoot a case of ammo to learn wind,’ or ‘train on a .308 to learn recoil.’ They sound convincing because they compress a lifetime of experience into a neat shortcut. But mindlessly dumping rounds downrange never produces lasting skill. Real progress comes from testing everything for yourself and paying attention to the layers hidden in that process. The proprioceptive feel of recoil, the sensory shifts of the wind, the percentage of shots that land where you intended. These layers reveal themselves only through attentive discovery. Science points the same way. Studies on the ‘generation effect’ show that people retain knowledge best when they generate their own answers instead of receiving them.

Discovery

As a coach, I’ve seen it repeatedly: when I give an answer directly, students might use it but rarely integrate it. I have largely given up on this approach simply because if someone comes to me for help I want them to walk away with real knowledge. With real knowledge and skill, when asked, they can point back to the time things changed for them. When I set up conditions for them to discover the answer, it becomes theirs—and it sticks. Educational psychology explains this through the ‘Zone of Proximal Development,’ described by Vygotsky, and Jerome Bruner’s theory of discovery learning. The idea is simple: learners grow most when they are close enough to reach the answer but must struggle to grasp it. ie Conscious practice and skill development. The Bjorks’ work on ‘desirable difficulties’ reinforces this: struggle feels slower, but it leads to stronger, longer-lasting skill.

Context

Another danger is the delusion of transfer. Hitting steel at a local range does not mean one is ready for sniper operations. Performing well in a match shows you prepared for that outlet. Preparing for a different outlet requires training with the skills and context unique to it. You rarely succeed by laterally transferring skills; instead, you have to adjust for each outlet. Doing that well takes experience—the kind that teaches you which parts carry over and which don’t.

Skills live in context, and when contexts change, so does the list of skill requirements. Over a century ago, psychologists Thorndike and Woodworth described the limits of ‘transfer of training.’. Skills rarely transfer beyond the specific overlap of context and task. Modern research in embodied cognition echoes this: knowledge is not abstract but grounded in sensory and contextual experience. By discovering the answer with careful queues and reinforcement someone will not only keep the learning curve steeper for longer; they will have context appropriate for what they are pursuing and that is important and invaluable for a student of the art.

Principles

I understand that everyone has their own philosophy on training. Remember that this is a mental framework you can rely on for growth. We validate every training rule through experience, and we build our skills so they repeat reliably in practice. To check for long lasting ways to grow ask yourself: if you can demonstrate this on demand and explain it well. When built on a framework of curiosity and exploration, someone will try a variety of different methods and in doing that come to know more than simply the drill themselves. This echoes the scientific publications on the subject who have concluded: Expertise does not come from hours alone but from mindful, repeated validation of specific skills.

Reflection

A master learns what truly works by paying close attention to the realities of skill, curiosity, and the lessons gathered along the way. Progress is slow, but it is real. Each principle that survives the test of experience becomes a door to the next stage of growth. Illusions shut those doors, while validation opens them.

Curiosity is a compass. Use it to remind, reorient, and guide yourself toward the habit of growth. Never forget that what we do is a practice, a lifelong quest in search of higher skill.