Join the Hide community

Get access to live stream, lessons, the post exchange, and chat with other snipers.

Register

Download Gravity Ballistics

Get help to accurately calculate and scope your sniper rifle using real shooting data.

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Maggie’s Funny & awesome pics, vids and memes thread (work safe, no nudity)

- Thread starter Lawless

- Start date

Also deduct the cost of crime, aid money which has been embezzled, etc.

I don't think the civil war was free, either.Also deduct the cost of crime, aid money which has been embezzled, etc.

The Rotunda of the University of Virginia.

Mosque?

No, it was designed by Jefferson. I believe its called Neo Classic Greek Revival architecture. His entire design was named 'The #1 example of original American architecture' by the ASA, the American Architect's Society, or some such. Quite a work of art, it was interesting to go to school there. Heres a better shot of the whole thing.Mosque?

jokeNo, it was designed by Jefferson. I believe its called Neo Classic Greek Revival architecture. His entire design was named 'The #1 example of original American architecture' by the ASA, the American Architect's Society, or some such. Quite a work of art, it was interesting to go to school there. Heres a better shot of the whole thing.

I wasnt offended. If youre ever in the area its well worth the tour.joke

I wasnt offended. If youre ever in the area its well worth the tour.

Would definitely tour it if I was near, it was a bit out of the way the last time I was remotely in the area.

Walked around the monuments and memorials in DC, skulked around the Hoover building, took in a few more sights, walked around Mount Vernon, ... all worth it.

Thats my one regret in leaving Virginia, I never got to Mt. Vernon. IMHO, GW was one of the outstanding figures not just in American history, but in world history. No Washington, no America, he was that critical. For a good read on him, if anyone's interested is His Excellency George Washington. Short easy informative read.Would definitely tour it if I was near, it was a bit out of the way the last time I was remotely in the area.

Walked around the monuments and memorials in DC, skulked around the Hoover building, took in a few more sights, walked around Mount Vernon, ... all worth it.

I never got to Mt. Vernon.

If you ever get the chance it's worth it. It's not all glitzed up (or wasn't when I was there), more like a day in the life of George. Kinda grounding experience, almost makes you believe in government again.

For the win.

I don’t have one, but the people behind me in traffic out on the highway might be wishing they had one. it seems people nowadays can’t stand to be behind someone who’s driving the speed limit/5 miles an hour over.Farbin air horn?

Sam’s Club has this little pressure washer on sale now(or at least last weekend) that has an included foam cannon to wash cars. Pretty handy and it’s especially nice to exploit the labor of your children

View attachment 1750469937926.jpeg

View attachment 1750469958961.jpeg

View attachment 1750469937926.jpeg

View attachment 1750469958961.jpeg

The last scene was very powerful

Currently watching Blackadder 2

All four seasons were enjoyable. For anyone that only knows of Rowan Atkinson from Mr. Bean it is quite different.Currently watching Blackadder 2

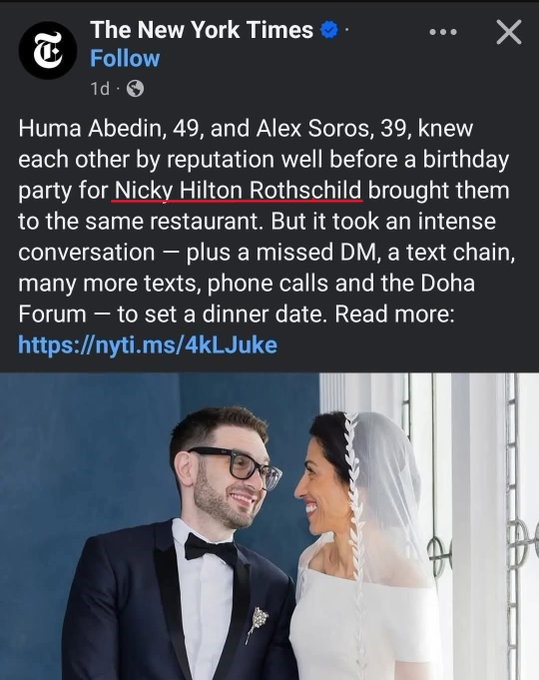

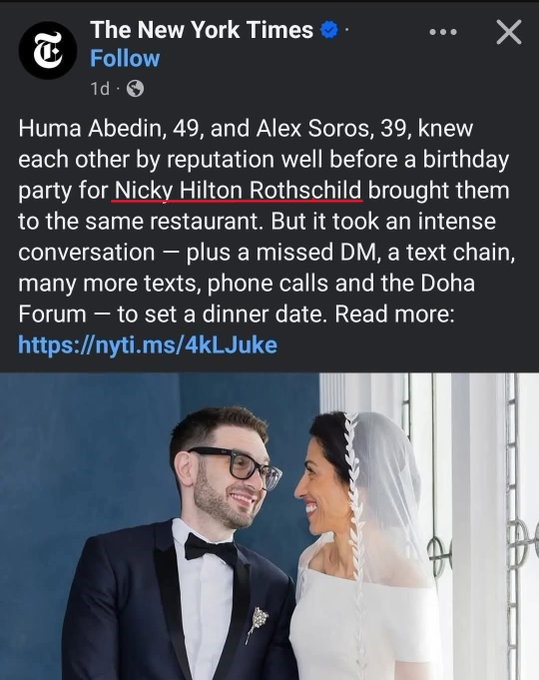

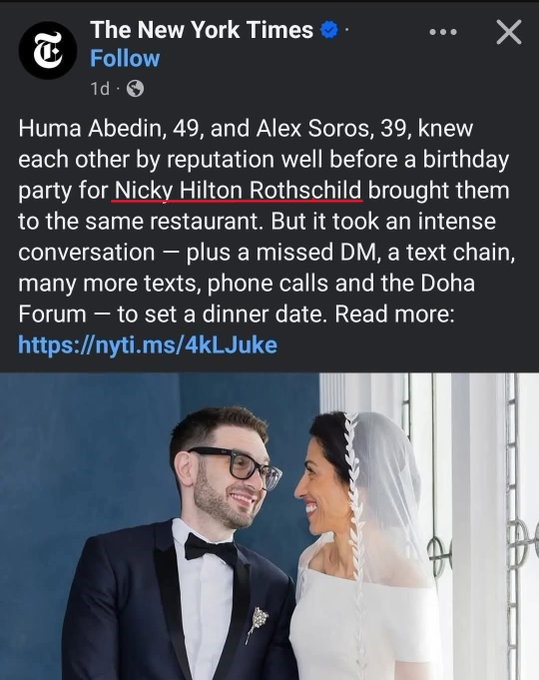

Clintons now control Soros , they hitched him with Wieners ex that was for decades Hillary Clinton's right hand

Made by Cat, should be good.Sam’s Club has this little pressure washer on sale now(or at least last weekend) that has an included foam cannon to wash cars. Pretty handy and it’s especially nice to exploit the labor of your children

View attachment 8712577

View attachment 8712578

My experience is 2100-2200 is enough for washing your car or really lightweight jobs but for tough jobs you really need 3200. Adjustabel is nice so you can use lower pressure when needed.

Last edited:

What Maggot asked ?Sam’s Club has this little pressure washer on sale now(or at least last weekend) that has an included foam cannon to wash cars. Pretty handy and it’s especially nice to exploit the labor of your children

View attachment 8712577

View attachment 8712578

They gonna be having an Ugly baby , if he’s capable! He’ll the spitting image of his piece of shit dad.Clintons now control Soros , they hitched him with Wieners ex that was for decades Hillary Clinton's right hand

Last edited:

Thats hits too close to home.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 17

- Views

- 943

- Replies

- 11

- Views

- 896